If you asked 10 people what Digital Public Infrastructure was, you would get 10 different answers.

Wikipedia says, Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) refers to digital systems and platforms that enable the delivery of services, facilitate data exchange, and support digital governance across various sectors.

India likes to consider itself the World Champion of Digital Public Infrastructure. If you ask, Aadhaar and UPI will be touted as examples of at-scale success.

When Aadhar was rolled out back in 2010. Literally nobody wanted to stand in queues at the post office to get the registration done. Countless coercion techniques were put to use. People were told that their bank accounts would be frozen if the Aadhaar was not connected to them. Income Tax filing would not be possible without connecting the account with Aadhaar. Then it turned out, there was no law that explicitly stated this.

India’s Supreme Court has come down heavily on the mandatory linking of Aadhaar for almost everything.

In a much-anticipated ruling today (Sept. 26), a five-judge bench struck down section 57 of the Aadhaar Act, which allowed corporate entities or even individuals to demand an Aadhaar card in exchange for goods or services. As a result, now no school, office, or company can force anyone to reveal the unique 12-digit number. Neither is it mandatory for opening bank accounts or for mobile connections.

Source: Quartz, July 2021

It took 10 years for the ruling to arrive, and in the intervening period of immense confusion, a billion people registered themselves on the identity platform.

The level of subterfuge and deceit involved in this Digital Public Infrastructure was not trivial. Not to mention, estimates have it that over $1 billion was spent by the government to roll out this platform.

The Internet is a digital public infrastructure. Nobody was coerced onto it. There was genuine usefulness and a large number of benefits that became inaccessible if one did not have it.

The other service that India likes to wave around is the Unified Payments Interface (UPI).

The only thing that makes UPI truly ‘Public’ is the large network of QR Codes that have been deployed by fintech companies in India. In the absence of that, UPI is no different from National Electronic Fund Transfer (NEFT) or Immediate Payment Service (IMPS). It is simply digital infrastructure. The creators of UPI had no role in making it public.

Fintech has been on the rise in India since 2015. In 2015, Credit card penetration was 1%, debit card usage was 10%; credit creation was poor, and banks were not structurally set up to address this. Micro-finance institutions had shown a path for democratisation of lending in rural areas; a similar push was envisaged towards the urban (not so poor).

Not to mention, the US had PayPal in 1999. In 2015, the collection of payments online was still quite difficult in India. The landscape was a duopoly. Even large established banks did not know what it took or how to go about offering payment gateways.

All these factors combined led to billions being poured into the fintech startups in India, which were simply bribing their customers into switching behaviour. 2%, 5%, 10% cash back. Why would one not switch?

Paytm introduced wallet-based payments that eliminated friction completely. It also introduced India to QR Code-based payments (peer-to-peer). Suddenly, it was possible to pay the fruit vendor, the autowala and many others with just a click on an app.

Against this backdrop, Demonetisation took place in 2016 and eviscerated urban India’s trust in cash.

In October 2016, INR 48.57 Crores (~ $7 million) was transacted over UPI.

By October 2017, that number was at INR 7057.78 Crores (~$1 billion).

Today, over INR 25,00,000 Crores (~USD 290 billion) is transacted each month over UPI.

Without demonetisation, I wonder where UPI would have been. I wonder where Paytm would have been!

In the case of UPI, the public interface was built by private companies. I challenge you to find BHIM QR Codes across any city in India.

Demonetisation was an opportunity to grab market share, and these companies sent out foot soldiers with missionary zeal to place QR Codes at every store and every outlet. Even the push-cart vegetable vendor has a QR Code on his cart.

Oh! Also, the foundation holding up this castle of card - Zero Merchant Discount Rate.

Typically, when you slide your card at a point of sale (POS) machine, 2% of the transaction value is deducted before payments are made to the merchant. That 2% gets shared between, say, Pine Labs, Visa, the bank which issued the card, and the bank that processed the payment. This 2% deduction is called the Merchant Discount Rate (MDR).

That is the allure of building a fintech company. So long as the infrastructure is working, you do not have to really do any work to earn the money.

After demonetisation, the government issued a diktat that reduced the MDR to zero on UPI. Every company/bank processing UPI just absorbs the cost for now. One day, someday, this will have to stop.

On the one hand, there is the fact that the infrastructure needed for UPI to operate at a USD 3 trillion a year scale can be managed with zero MDR shows the crazy margins financial companies make. On the other hand, once the diktat is removed, greed will quickly set in, and the true test of this “public good” will begin.

NPCI is a quasi-banking institution, which is a fancy way of saying that it’s not a bank but acts like one. It is owned by all of the large banks in India, which are stakeholders. The bank processing the payment and accepting UPI is private. The companies creating the final layer of QR codes to enable acceptance of payments are private. So what the hell is “public” with UPI?

The absence of the MDR creates a false sense of public ownership, while it is anything but.

In short, UPI is a digital infrastructure run but private companies for the public. You know, usually they are known as technology companies. In India, we make many banks own the technology and just call it Digital Public Infrastructure.

So when I keep coming across this term DPI, I don’t even know what they are talking about.

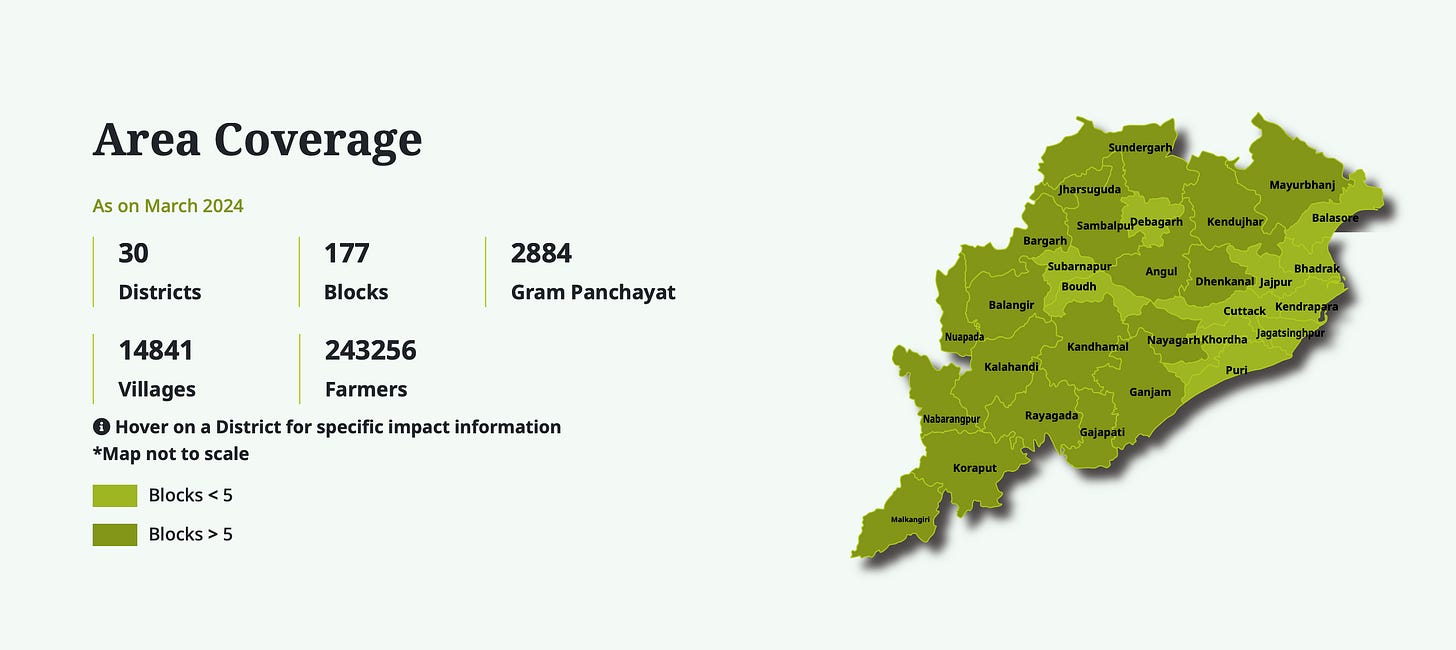

In the meantime, the Orissa Millet Mission, about which not even a Wikipedia page exists, managed to onboard over 200,000 farmers across more than 14,000 villages and got them to register themselves through the gram panchayats to make their produce available for the Public Distribution System.

The cropping pattern across a state was shifted from rice to millets and resulted in sustainable water abundance.

Source: Shree Anna Abhiyan

Nobody was forced or coerced; no private organisation had vested interests; no incentives or cashbacks were offered. The government, along with an NGO called WASSAN, worked to produce systems change. They spent months engaging farmers, helping them understand hydrology, agroecology and economics. They created the digital tools that could allow this to scale. The results are undeniable.

Growing an acre of Ragi requires about 100,000 litres of water.

Growing an acre of Rice requires about 1.2 million litres of water.

Ragi procured by the Orissa government alone went from 5,000 quintals in 2018-19 to 760,000 quintals in 2024-25. All of it was accomplished using a digital backbone. This is Digital Public Infrastructure.